In a heartbreaking turn of events on May 12, 1932, the lifeless body of Charles Lindbergh’s infant son was discovered, over two months after being snatched from the Lindbergh family’s residence in Hopewell, New Jersey.

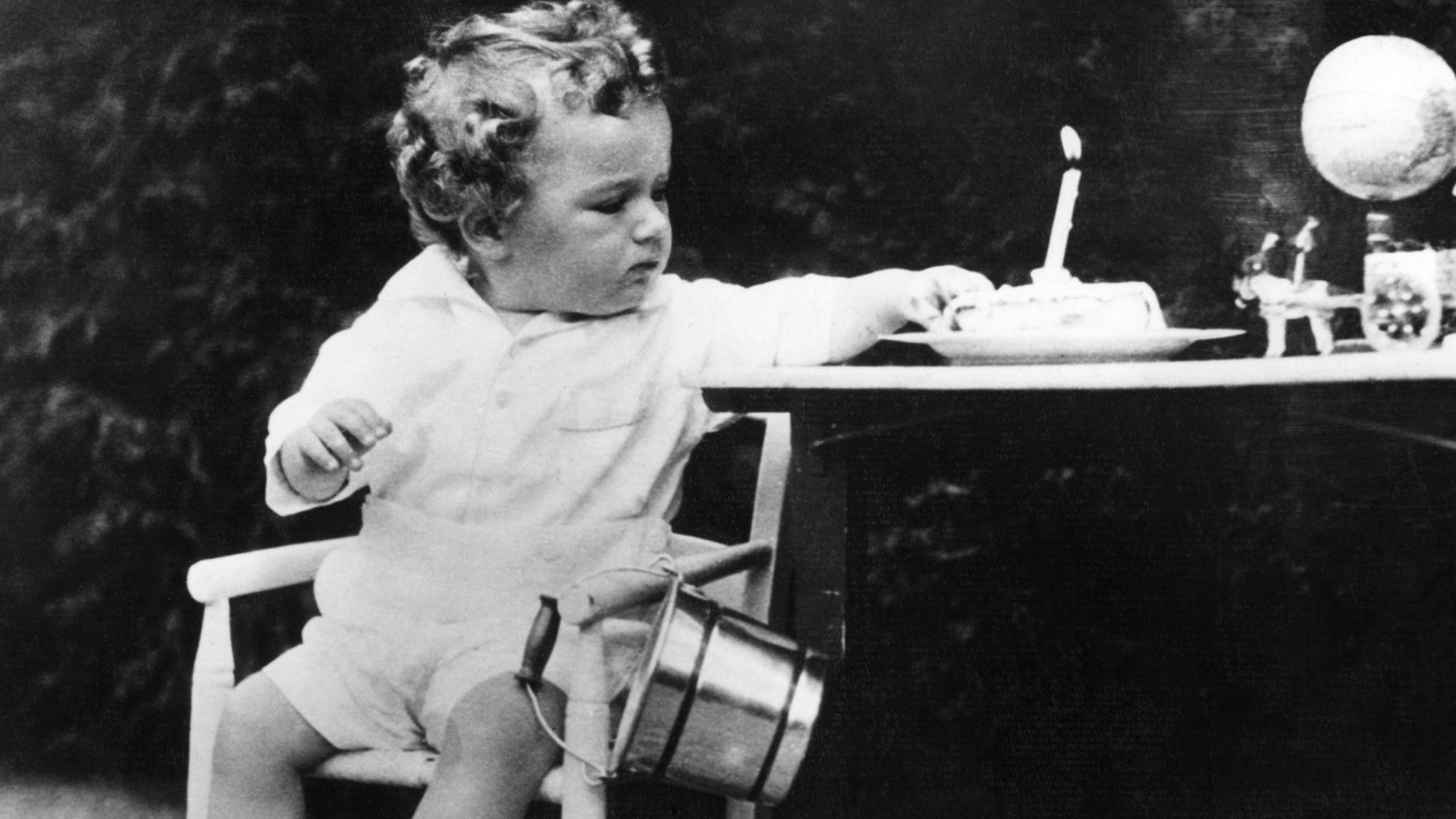

Charles Lindbergh, renowned for his historic solo flight across the Atlantic that catapulted him to global fame, alongside his wife Anne Morrow Lindbergh, stumbled upon a ransom note in their 20-month-old child’s unoccupied bedroom on March 1.

The kidnapper had utilized a ladder to access the open second-floor window, leaving behind muddy footprints and a poorly written ransom demand of $50,000.

The nation was captivated by the heinous crime as the Lindbergh family was inundated with offers of support and false leads.

Notable figures, including the infamous Al Capone from prison, extended assistance, albeit under certain conditions.

Despite relentless efforts, three days passed without any progress until a subsequent letter surfaced, escalating the ransom to $70,000.

On April 2, the abductors provided instructions for the ransom drop-off.

However, upon delivery, the perpetrators claimed the child, baby Charles, was aboard a vessel named Nelly off Massachusetts’ coast.

Despite an extensive search of all ports, neither the boat nor the infant were located.

A tragic twist unfolded on May 12 when the baby’s lifeless body was discovered near the Lindbergh estate, revealing that the child had met his demise on the night of the abduction, merely a short distance from home.

Overwhelmed with grief, the Lindberghs eventually donated their mansion to charity before relocating.

The case seemed destined to remain unsolved until September 1934, when a marked ransom bill resurfaced, leading suspicions to a gas station attendant who noted the license plate number of the individual who tendered the bill.

This trail led to Bruno Hauptmann, a German immigrant, in whose possession $13,000 of the ransom money was uncovered during a search of his residence.

Hauptmann professed innocence, claiming a friend entrusted him with the funds with no involvement in the crime.

Subsequently, a highly publicized trial ensued, attracting coverage from renowned journalists Damon Runyan and Walter Winchell.

Despite a somewhat circumstantial case, including handwriting analysis linking Hauptmann to the ransom note and ties to the ladder’s construction material, intense scrutiny and evidence led to Hauptmann’s conviction.

In April 1936, Hauptmann faced the electric chair for his alleged role in the kidnapping and murder.

The aftermath of this notorious incident prompted the federalization of kidnapping as a criminal offense, marking a significant legal development spurred by this tragic chapter in history.