In the heart of El Salvador lies a facility that pushes the boundaries of what we think a prison can be.

Known as the Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo, or SECCOT, this super-prison spans an astonishing area equivalent to seven football fields and has the capacity to house up to 40,000 inmates.

You might be wondering how such a vast number of individuals can be accommodated.

Think of it like a meticulously organized warehouse, where every inch of space is utilized efficiently.

El Salvador, once regarded as one of the most dangerous countries globally, has seen a dramatic transformation under President Nayib Bukele’s leadership.

In a remarkably short time, he has managed to turn his nation into the safest in Latin America by capturing and imprisoning the notorious cartels and mafias that plagued the country.

Here, these criminal organizations are labeled as terrorists, and Bukele’s response was to construct SECCOT—a prison designed to minimize inmate comfort and maximize security.

Although SECCOT was completed about a year ago, it currently houses around 13,000 prisoners, leaving ample room for more.

The conditions within these walls are stark.

In the eyes of the officials, inmates are not seen as human beings but rather as “terrorists.” This dehumanization reflects a broader philosophy regarding crime and punishment in the country.

Approaching SECCOT is no simple task.

The prison is situated in a remote area and guarded by seven rigorous checkpoints, beginning a kilometer away from the facility.

Journalists attempting to enter are subjected to thorough searches, including stripping down to ensure they carry nothing illicit.

Vehicles are inspected meticulously, and only after passing all checkpoints can one finally reach the entrance.

This level of scrutiny is unmatched, akin to boarding a plane but with even stricter measures in place.

Once inside, the reality of SECCOT becomes even more severe.

Inmates have no visitation rights, not even from their lawyers.

Any necessary communication is conducted through video calls in designated rooms, effectively severing prisoners from outside contact, including family.

Additionally, powerful jamming devices ensure that no mobile phones or wireless communications can penetrate the prison walls, further isolating the inmates.

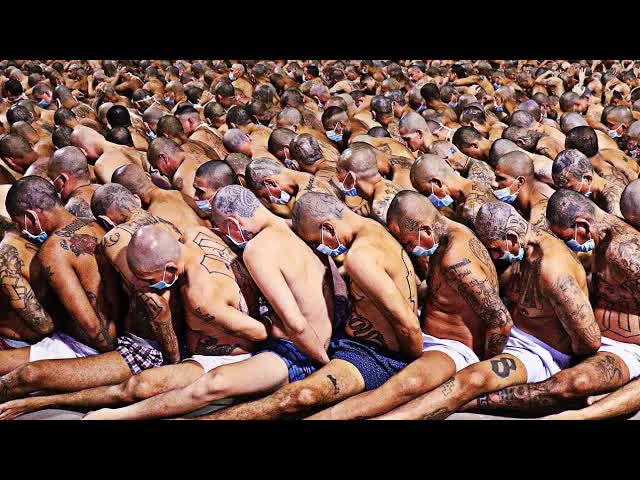

The intake process for new prisoners is equally intense.

They undergo comprehensive searches, including X-rays that can reveal anything hidden within their bodies.

Once cleared, they receive a uniform, a blanket, and a towel before being escorted to their cells, where they are restrained and forced to look at the ground.

Guards typically do not carry firearms, relying instead on batons, while armed guards monitor the premises from above.

The living conditions at SECCOT are harrowing.

Cells are massive, often accommodating up to 100 inmates without any privacy for essential functions.

There are no enclosed toilets or showers; instead, a single toilet is openly shared among all.

Beds consist of metal shelves without mattresses, forcing inmates to use their towels for comfort.

The absence of natural light and constant bright artificial lighting adds to the psychological strain, making it nearly impossible for inmates to determine the time or day.

While capital punishment exists in El Salvador, it does not apply to terrorism-related crimes.

Instead, many inmates face sentences that stretch into thousands of years, with only a rare few receiving shorter terms.

The lights in SECCOT never turn off, creating a perpetual state of discomfort and confusion, which can lead to heightened anxiety among the prisoners.

For those who misbehave, punishment involves being sent to a dark isolation cell known as the “black hole,” where they endure complete darkness and minimal contact with the outside world.

Their meals consist primarily of bread and boiled beans, served in plastic containers, with no utensils provided.

This stark diet is designed to strip them of any remaining dignity.

In contrast to prisons in other Latin American nations, where inmates often exert control over their surroundings, SECCOT operates under a different paradigm.

The government has taken a firm stance against corruption and violence within its prison system.

Officials remain anonymous to protect their identities from potential cartel reprisals, highlighting the ongoing threat posed by organized crime.

Despite the grim portrayal of life within SECCOT, the El Salvadoran government asserts that the prison is not yet at full capacity.

With room for thousands more, this statement serves as a deterrent to potential offenders, reinforcing the idea that there is no escape from the consequences of their actions.

As the nation continues to navigate its path toward safety and stability, SECCOT stands as a testament to the lengths to which the government will go to reclaim control from the clutches of terror.