Long before Secret Service agents safeguarded the president, they pursued counterfeiters.

Their focus shifted officially in 1894, when a few agents took on the role of Grover Cleveland’s bodyguards.

However, there exists an earlier instance of the Secret Service engaging in presidential security, albeit momentarily and in a unique way.

In 1876, Abraham Lincoln’s remains rested in an aboveground white marble sarcophagus within a beautiful tomb at Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, Illinois.

Positioned around 2 miles outside the town, Oak Ridge was a rural burial ground devoid of a resident groundskeeper or a nighttime watchman patrolling near the president’s tomb.

The only barrier between Lincoln’s body and potential grave robbers was a lone padlock securing the tomb’s chamber door.

Not even the sarcophagus itself was theft-proof, as its lid was sealed not with concrete but the less permanent plaster of Paris.

To the esteemed gentlemen of Springfield who belonged to the National Lincoln Monument Association responsible for upkeeping Lincoln’s tomb, the lack of stringent security measures seemed rational.

Who, after all, would desire to snatch Lincoln’s body?

The unexpected answer to that query lay with a gang of Chicago Irish counterfeiters led by a minor crime figure named Big Jim Kennally.

Early in 1876, Kennally sought to release his top engraver of fake plates, Benjamin Boyd, sentenced to a decade in Joliet, Illinois.

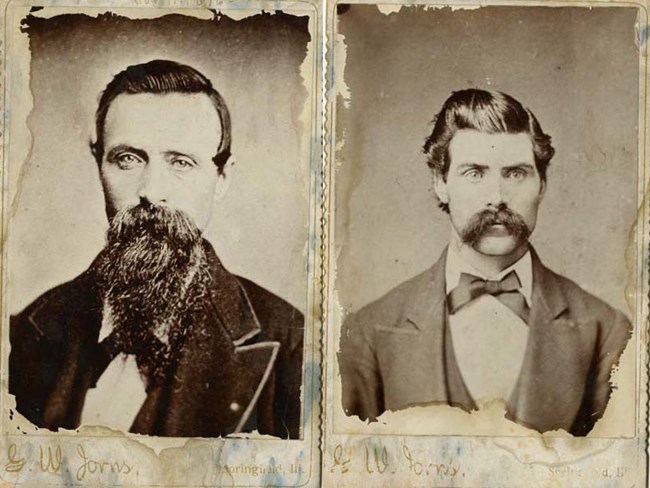

To pressure the governor into granting Boyd clemency, Kennally enlisted two gang members, Terence Mullen, a saloon owner, and Jack Hughes, an occasional producer of counterfeit coins, to abduct Lincoln’s body.

They planned to demand $200,000 in cash and Boyd’s full pardon as ransom.

Given the lax security at the cemetery, the gang stood a good chance of executing the heist successfully.

Yet, a critical error was made.

Mullen and Hughes, lacking experience in body snatching, recruited a man named Lewis Swegles, whom they believed to be a grave robber.

Unfortunately for them, Swegles was a paid informant for the Secret Service, acting as a double agent.

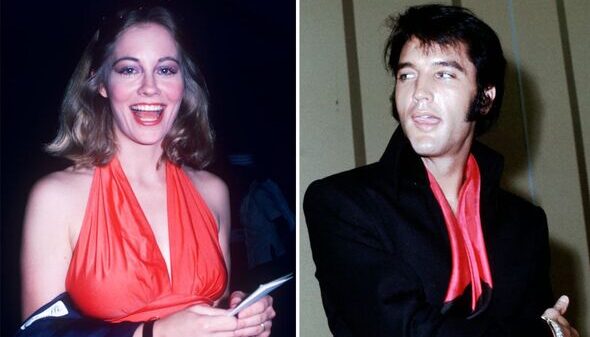

Swegles performed his part adeptly, feeding every detail of the scheme to his superior, Patrick D. Tyrrell, head of the Secret Service’s Chicago district office.

When Swegles accompanied Mullen and Hughes to Oak Ridge Cemetery, Tyrrell and his agents lay in wait at Lincoln’s tomb, preparing to witness the unfolding comedy of errors.

Despite their criminal backgrounds, Mullen and Hughes struggled to pick the lock, resorting to cutting through it with a file.

Inside the tomb, they found themselves unable to lift Lincoln’s 500-pound coffin made of cedar and lead.

As they deliberated their next move, a detective’s gun accidentally discharged outside, prompting Mullen and Hughes to flee back to their Chicago saloon, where Tyrrell arrested them a few days later.

Meanwhile, in Springfield, the tomb’s custodian, John Carroll Power, was gripped with fear.

If amateurs could come close to absconding with Lincoln’s body, what might skilled body snatchers achieve?

Power’s sole solution was to conceal the body where none could discover it.

Under the cover of night, Power and five acquaintances buried Lincoln in a shallow, unmarked grave within the tomb’s basement.

Despite not having known Lincoln personally, the men who interred the coffin felt a deep sense of duty to protect his remains.

They vowed never to disclose the whereabouts of the revered president’s body and upheld this pledge faithfully over the ensuing years.

Their obligation concluded in 1901, following instructions from Robert Lincoln, the president’s sole surviving child.

Lincoln’s remains were encased in a steel cage, lowered into a 10-foot-deep vault, and concealed under layers of damp concrete.

To this day, Lincoln rests in his tomb on the grounds of Oak Ridge Cemetery.

Although Tyrrell emerged as the hero of the failed scheme, the Secret Service arguably reaped the greatest benefit from the thwarted crime.

Safeguarding Lincoln’s body ultimately paved the way for protecting the presidency itself.