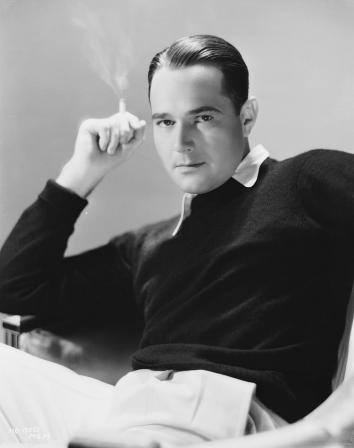

William Haines, a silent film star, is often remembered as the first openly gay Hollywood icon.

According to popular belief, he was fired by Louis B. Mayer, head of MGM, for refusing to give up his live-in boyfriend and marry a woman.

While there is some truth to this account, the reality of Billy Haines' life in Hollywood is far more complex.

Born on the cusp of the 20th century, Haines thrived during the exuberant Roaring '20s.

However, he struggled to adapt to the limited opportunities of the following decade.

Eventually, he reinvented himself and capitalized on the prosperity and consumerism of the midcentury.

Throughout it all, he proudly celebrated his status as one-half of Hollywood's first openly gay marriage.

From 1926 to 1931, Haines achieved immense success as a box office sensation with hits like “Brown of Harvard” and “Tell It to the Marines.”

By 1929, Irving Thalberg, Haines' studio boss at MGM, hailed him as the embodiment of youthful masculinity and a new type of romantic leading man.

Thalberg declared, “The idealistic love of a decade ago is not true today.

William Haines, with his modern salesman attitude to go and get it, is more typical.”

By this time, the entire Hollywood community, including Thalberg, was aware that Haines was effectively married to a man.

In 1926, during a trip to New York, Haines had a whirlwind romance with Jimmy Shields, a former sailor.

Haines brought Shields back to Los Angeles, where they lived together openly.

They even became part of the elite inner circle surrounding Marion Davies and William Randolph Hearst, receiving regular invitations to San Simeon.

Although the local movie press knew about their relationship, no one dared expose it.

Any journalist who did so would have been ostracized from MGM for eternity.

At that time, as long as they weren't hurting anyone, nobody cared.

When asked about his love life, Haines would cleverly deflect the question with a humorous remark.

Journalists and subjects would exchange knowing glances, and Haines would be portrayed as an eligible or confirmed bachelor in print.

Everyone would simply move on.

In response to a voice coach's comment that he had “lip lazy” vocal technique, Haines wittily retorted, “I've never had any complaints before.”

Interestingly, Haines was better equipped than many other stars to transition into talking films.

His voice was strong and devoid of thick accents.

Moreover, his signature in silent films had been his witty intertitles, which made it seem as if he possessed impeccable comedic timing.

In truth, he did have this talent, and he effortlessly transferred it to his performances as a talking comedian.

Haines seamlessly adapted to the advent of sound in film, and 1929 became the pinnacle of his box office success.

However, challenges lay ahead.

In 1930, all Hollywood studios agreed to abide by the moral guidelines outlined in the Hays Production Code.

Nevertheless, the code lacked enforcement capabilities, leading to racier films.

However, the existence of the code made studios more inclined to utilize morals clauses in performers' contracts to regulate public behavior.

While most stars signed these contracts and either avoided trouble or assumed the studios wouldn't enforce the clauses, Haines took a different approach.

At the height of his stardom in the late 1920s, he reportedly refused to sign his contract until the morals clause was removed entirely.

In exchange, MGM offered him only two-year extensions instead of the standard five-year contracts.

Haines' films began to decline in popularity throughout 1930, and in 1931, MGM terminated his contract.

However, they rehired him as a featured player at a significantly reduced salary and billing.

In an attempt to rebrand Haines from a wisecracking college boy to a more mature romantic lead, he was cast in the film “Just a Gigolo.”

Although instructed to abandon his usual winking and wisecracking persona, he disregarded this directive.

Despite featuring the song later covered by David Lee Roth, “Just a Gigolo” failed to reverse the perception that Haines' star was fading.

Consequently, his contract was not renewed, and trade papers claimed it was due to his desire for higher pay.

Eventually, MGM agreed to bring Haines back, albeit at a lower salary and with demoted billing.

He was compelled to embark on a personal appearance tour, leading him to adopt a rigorous diet and exercise regimen in an attempt to appear younger and fresher.

According to some accounts, in early 1933, Louis B. Mayer summoned Haines to his office and demanded that he end his relationship with Jimmy and get married.

Allegedly, Haines responded, “I am married,” choosing Jimmy over Mayer and leaving the office.

He subsequently became Hollywood's most sought-after interior designer.

Following his departure from MGM, Haines indeed became a highly sought-after interior designer.

The details of the remainder of his story, however, are subject to debate.

Some members of the gay Hollywood scene believe that Haines sacrificed himself for Jimmy, who had been arrested while engaging in public cruising.

If true, this incident was effectively covered up.

What is known is that Haines' star had dimmed, he was growing older, and he had not successfully transitioned away from his Harvard-boy image.

The economic depression had studios concerned about profit margins, leading them to cut salaries or cancel contracts of aging stars.

While many other stars in Hollywood were involved in gay relationships, most presented themselves as heterosexual when required.

For instance, it is now widely acknowledged that Haines' friend Archie Leach (later known as Cary Grant) lived as a gay man before and during his early years in Hollywood.

Nevertheless, Grant, like many others, adhered to the rules established by Louis B. Mayer and the other studio moguls.

They were willing to marry women, even multiple times, and keep their